Better by Design: The Best Designed Apple Laptops

September 16th 2002

What were the best -designed PowerBooks? Not the most popular, not the best-looking, not the most expensive.

Charles Moore's recent article at MacOpinion asked what features we'd like to see on the next-generation PowerBook G4. That got me thinking about form and function of previous PowerBooks and iBooks. But how do we define these?

Form: how well does the 'Book's design fulfill the purpose for which it was intended? Naturally, form may simply be designed to look cool, business-like or be designed down to a particular weight or size. How many drives, batteries, slots and what size screen will heavily influence form.

Function: how well does the 'Book perform its intended function? You might well argue that a portable is a portable is a portable. But some laptops clearly do this better than others. Why? Our criteria here might be how well the Power/iBook functions as a desktop replacement without too many compromises. Equipment here is important; a notebook with no removable storage is not as practical as one with a floppy. Equally, a CDRW-equipped portable has a wider degree of flexibility and functionality than one with a mere floppy.

Innovation: does the 'Book provide innovative features, or is it a me-too notebook? Does it provide significant technological advances over the previous generation of Mac portables?

These are clearly subjective criteria, not professional design parameters. But the aim here is to consider portables from the point of view of the end user - this is what is important. You don't just buy a PowerBook or iBook because it's a Mac; you don't necessarily even buy it because it's a technological tour de force.

You buy it because it fulfills your notebook needs more closely than any other market entry - within your price range, obviously. The reason the original PowerBook 100/140/170 sold over 300,000 units in less than 12 months was because its design was due to its innovation. It was far from the fastest on the market (especially the 100) and was very expensive (until the 100s were discounted as they reached EOL). The 030s were toasted by 486s and they offered no color displays for the first two years. But the palm rests, SCSI docking convenience (and the Mac OS) sold them by the boatload until they became wildly uncompetitive.

So these are the narrow, yes, subjective lenses through which we'll look at these Mac portables. But it can be about taste as much as anything else: Woz, for example, regards the TiBook (and the Cube) as the greatest Macs ever. I don't know his criteria. But I'm betting that there are some hacked-off Ti and Cube owners who would vehemently disagree. Even with Woz.

iBook (original) (1999-2001)

The first iBook, initially available in Tangerine and Blueberry, gets the nod here for a number of innovative new features, never previously available on the Mac, although some became available on subsequent Macs. Designed principally for the school/college market, over 600,000 were sold as Apple priced it as a stripped-down consumer portable.

The first iBook, initially available in Tangerine and Blueberry, gets the nod here for a number of innovative new features, never previously available on the Mac, although some became available on subsequent Macs. Designed principally for the school/college market, over 600,000 were sold as Apple priced it as a stripped-down consumer portable.

The first was the oval design, the infamous 'toilet seat'. iBook's rounded edges made it more impervious to shocks than squared-off designs, and its polyurethane shell made it generally more scratch and crack-resistant than any other previous Mac - and probably any other PC notebook (not including notebooks made for industrial/scientific purposes, which are specially ruggedized).

Tough? Strong enough to withstand severe mistreatment at the hands of 5-to-50 year olds. Schoolbags, drops, knocks - the iBook could take it. Of all the notebooks I've ever dealt with or serviced, I'd have to say it's the most trouble-free. When no one brings one in to fix, to replace a case plastic or whatever, you can tell that AppleCare probably loves these babies; nothing breaks. Yes, the key caps broke off early models, but the hinges are incredibly strong.

The downside to this is weight: well over 7 pounds of it, something Apple couldn't overcome until it moved to an entirely fresh iBook design. However, original iBook owners will swear their models are much tougher than their successors.

Integral to the design strength, and also a key part of the iBook's form and function is the foldaway handle. Phil Schiller demonstrated its strength on release in 1999 by jumping off stage and swinging it around his head. As a security device, it meant you could secure the iBook's handle to a desk and know that no one could walk off with it.

iBook also emphasized hardware/software integration. In an Apple portable first, it had no screen latch, but held together firmly like a jewel case. It slept when you closed it (like all PowerBooks), but woke up when you opened it. It could automatically save contents to RAM (after a bug fix solved the problems in the original 8.6(.1) release. Rather than having the enternally-breaking rear port cover, iBook did away entirely with the cover. Plug right in, a feature carried over to the current iBook.

Also innovative was the under-the-hood wireless connectivity: Airport to you and me. An Apple industry first, the iBook led the PC market by at least 12 months with this feature alone. The iBook had no PC slot and no dongle to break or snag, while the antenna was built into the handle. The fact that the iBook was otherwise a little lackluster in the equipment department was offset by the wide variety of innovation the original iBook demonstrated.

PowerBook 500 Series (1994-95)

Business-like and high-tech, the 500 was built for the corporate environment and carried an enterprise price-tag: around $5,000 for the top-of-the-line 540c. It was good-looking and innovative enough to woo some of the DOS/Win 3.1 crowd to tote a Mac portable, even if they had to look through Windows at work.

Business-like and high-tech, the 500 was built for the corporate environment and carried an enterprise price-tag: around $5,000 for the top-of-the-line 540c. It was good-looking and innovative enough to woo some of the DOS/Win 3.1 crowd to tote a Mac portable, even if they had to look through Windows at work.

Flying buttresses and sharp angles distinguish the 500 series from virtually any other PowerBook. Perhaps only the G3 Series, the TiBook and the fruity iBooks have been as daring in their looks - and the latter three designs are much more understated, conservative designs than the 500.

What's more, the 500 had a removable CPU daughtercard, allowing for PowerPC upgrades (eventually, up to the always-rare 183MHz Newer upgrade).

It's difficult to work out whether loading a model with fruit qualifies it for the 'innovative' tag. But in the case of the 500, it undoubtedly did, as many were industry firsts. The 9.5" 16-bit 540c display was one example, albeit at only 640x400. The twin NiMH 'Type III 'Intelligent' batteries, giving around 5-6 hours' work time. The left-hand battery bay could take an optional dual- PCMCIA slot cage connected via a 32-bit PDS. Although standard on many PC notebooks, this was the first PCMCIA Mac portable.

Not that the 500 had much use for PCMCIA at the time. The modem was the faster 19.2kbps model available at the time. 10bT ethernet was built in, as was video out to monitors up to 20" (with separate VRAM for operating external displays), virtual desktop or mirror mode, SCSI, and serial/LocalTalk connectivity. A row of Function keys ran across the upper reaches of the keyboard. To top it all off, the 500 dumped the PowerBook 100 and 200 Series trackball for a solid-state trackpad (tappable with software).

Not that the lower-end models were short changed. The 520 and 520c sported slightly slower 68LC040 processors, and less impressive passive-matrix screens, but exactly the same feature set as the 540 and 540c (the modem was optional).

At over 7 pounds, the 500 was no lightweight, but it was well within the ballpark of comparable high-end notebooks at the time. And even today, almost 10 years on, many Wintel notebooks still don't have ethernet as standard. A yardstick? Arguably, the benchmark by which many Mac and PC portables were judged for many years. Indeed, by comparison, Apple's successors to the 500, the 190/5300 and 1400, were considered lackluster in the equipment and innovation departments.

PowerBook 100 (1991-92)

Historical narratives vary on the extent to which Apple and/or Sony had responsibility for this sure-fire hit, but the Apple Portables group stakes the greatest claim. When the baby turns out well, everyone claims paternity. Sony built it, but the small group that led PowerBook design (and coined the name) wrote the design spec in the wake of Jean-Louis Gassée's Portable fiasco of 1990.

Historical narratives vary on the extent to which Apple and/or Sony had responsibility for this sure-fire hit, but the Apple Portables group stakes the greatest claim. When the baby turns out well, everyone claims paternity. Sony built it, but the small group that led PowerBook design (and coined the name) wrote the design spec in the wake of Jean-Louis Gassée's Portable fiasco of 1990.

Unlike the enormous, clunky PC portables of the late 1980s and 1990s (to see the Mac clone equivalent, look at the Outbound), the 100 was thin and light - still light by modern standards, at around 5 pounds. Arguably the most brilliant innovation was the keyboard-forward design, providing large, comfortable palm rests. No other portable did this, and many resisted it for some time afterwards, until the 100-series as a whole proved a huge sales success. In practice, every notebook built today is essentially based on the PowerBook 100. That, in itself, demonstrates the extent of its design impact. A passive-matrix LCD was used to keep the price down (the Portable's was active-matrix, but raised the cost and retail price considerably).

Not content with this, Apple/Sony developed SCSI Disk Mode (SDM), so the 100 could be docked with virtually any Mac desktop with a simple cable. The 100 had its SDM in burned into ROM, (Sony figured it out), while the 140/170 didn't have this capability, as Apple were still working out the instructions for the 140/170 to operate in tandem with the forthcoming Quadra/Centris series. The next revision of PowerBook (160/180) got SDM back. The 100 of course employed a 2.5" SCSI hard drive, which gave it superior performance to IDE-equipped PC portables. The 16MHz 68000 CPU, while obsolete, was still twice the clock speed of any Mac 68000 desktop, like the Classic, which was still on the market. It also held up to 8MB RAM, much more than most PC portables.

To keep the 100 thin and light, the floppy was external, something true of most sub-notebooks today when it comes to optical drives. This detracts from the overall functionality of the design, but not unduly.

PowerBook G3 (Wallstreet) (1998-99)

A basic design so good that it lasted almost 3 years. It paved the way for its thinner/lighter Lombard and Pismo successors, but they retained its essential form and dimensions.

A basic design so good that it lasted almost 3 years. It paved the way for its thinner/lighter Lombard and Pismo successors, but they retained its essential form and dimensions.

Wallstreet was the first truly Jobs-Ive portable production to come out of Cupertino - and it showed. The earlier 5300, 1400 and 3400/Kanga models were rectangular slabs of charcoal, by and large. So was the Wallstreet, but with major stylistic differences: the curved form gave the 'Book solidity, strength and a resistance to cracking when dropped. Two deep, full-length grooves were carved into the top case and underside, with centers formed of rubberized, high-grip plastic. The palm rests were similarly coated (which caused problems with ageing on the Wallstreet I). Like the 500 series, the Wallstreet gave users back dual expansion bays, for ultimate flexibility: twin 3-hour batteries, or a floppy and a CD/DVD ROM were possible, along with Zip or additional hard drives.

The bar was raised considerably in the functionality department over its 3400/Kanga predecessor: S-video out on most models, dual CardBus slots, scissor-action keyboard (from the 2400 design).

PowerBook 3400 (1997-98)

Possibly a questionable choice, but the 3400 was packed with innovation, both internally and externally, at least as far as Apple portables are concerned. The 3400 was most notable for the technological firsts (for Apple) for a Mac portable: PCI architecture; a CardBus controller (not advertised by Apple, but very usable today for USB cards); 24-bit colour on the internal display; a four (count 'em, four) speaker system; LiION batteries (which had appeared very briefly, and never in consumers' hands, on the 5300); Zoomed Video through the lower PC card slot, allowing video-in cards, such as the Capsure; an improved EIDE controller; 4Mbps IrDA; a custom Fast SCSI controller with SCSIManager 4.3 (at last!) in ROM; and a combination 10bT Ethernet/modem card that fitted into a mini-PCI slot (made by Fallaron).

While the 3400's chassis was essentially a stretched 5300 (and, rumor has it, built partly out of unused 5300/190 case plastics), it made up for its unremarkable heritage by being backwards-compatible with 5300/190 expansion bay drives and NiMH batteries, as well as having an interchangeable keyboard and many other case components.

The 3400 is worthy of inclusion here because it provided so many under-the-hood innovations not immediately apparent at first inspection. These made the 3400 much more comparable with desktops of the time. Yes, it does fulfill its design objectives: price-no-object; all desktop features in a portable package; fastest laptop available anywhere on any platform (true for a few months). The 240MHz model was blazingly fast for the time, and faster in many tests than competing Pentium notebooks. The very similar Kanga G3 '3500' model added little but the G3 and some minor tweaks, but was obviously a better-performing 'Book, even if it added little by way of innovation beyond being the first factory G3 Mac portable.

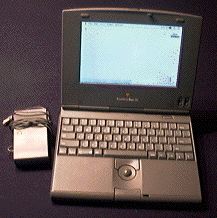

PowerBook Duo 200 Series (1992-96)

BOBW (Best of Both Worlds), the Duo's code name, exemplified its innovative approach to solving the portable/desktop puzzle. By buying a Duo plus a Dock, you didn't need to buy two Macs, Apple reasoned. But of course there was a catch: the prices of the Duo and the Dock were around the price of two new Macs.

BOBW (Best of Both Worlds), the Duo's code name, exemplified its innovative approach to solving the portable/desktop puzzle. By buying a Duo plus a Dock, you didn't need to buy two Macs, Apple reasoned. But of course there was a catch: the prices of the Duo and the Dock were around the price of two new Macs.

In many respects, the Duo was vastly superior to its 100 Series brethren. The base 210 model clocked in at 25MHz, much faster than the 16MHz 140, although the 145, introduced at the same time, was just as quick. It used more advanced memory, allowing for a 24MB maximum capacity initially, and higher capacities with high-density cards later on. By contrast, the 100 Series was stuck at a mere 8MB for the original 100/140/170 models, and a still-paltry 14MB on the succeeding 160/180 models.

The Dock gave the Duo advanced capabilities, unattainable on any of the 100 Series. NuBus cards, additional hard drives, ethernet and big monitor support took the Duo places (accelerated video graphics cards for a start) that the 100s could not hope to go.

In the display department, early Duos were disappointing, employing passive matrix screens to keep the price down. The line improved gradually, with the active matrix 250 and 270, color on the 270c and excellent active color on the 280c and 2300c. The innovative set of peripherals the Duo produced - by both Apple and third-party manufacturers - included the MiniDock, the MicroDock, and the floppy adapter. You could have as much, or as little, connectivity as you wanted with the Duo.

iBook (Dual USB) (2001- )

What strikes one about the icy iBook is its very minimalism. But this minimalism exudes function. It lools efficient in its design and it is. Glossy, with sharply-defined edges, the iBook has no protruding parts when the CD/DVD bay is closed. By way of comparison, the G3 series is replete with two front-mounted expansion bay levers, a modem on the side on the Wallstreet, and a flip-open port door at the rear. A number of grooves and a general 'busyness' about the case plastics tends to exude their business-like, full-featured, professional nature.

What strikes one about the icy iBook is its very minimalism. But this minimalism exudes function. It lools efficient in its design and it is. Glossy, with sharply-defined edges, the iBook has no protruding parts when the CD/DVD bay is closed. By way of comparison, the G3 series is replete with two front-mounted expansion bay levers, a modem on the side on the Wallstreet, and a flip-open port door at the rear. A number of grooves and a general 'busyness' about the case plastics tends to exude their business-like, full-featured, professional nature.

The iBook has no port doors, but that is where its similarity with the original iBook ends. Gone are the gaudy colors, the two-tone plastics and that major design innovation, the fold-in carry handle. The very absence of CardBus slots suggests that the iBook is - and it is - an all-in-one closed box, self-sufficient. Peripherals (ethernet/phone cables, FireWire drives, USB printers) plug in, but their are inherently separate from the iBook.

The feature set lends itself to the iBook's self-contained functionality as well. For the first time, this Apple portable offers an internal CDRW and a DVD/CDRW Combo drive. No longer is it necessary to carry around a portable Zip, CDRW and the associated cables and power supplies. This is the point Apple conveyed with great success: you don't need to buy anything else. Everything necessary is contained within that small white tablet.

A weight of 4.9lbs makes the iBook almost as light as the Duo 200 series, with a great deal more connectivity. But a larger keyboard than the 2400 or 200/2300 means the iBook functions much more acceptably as a sub-notebook.

Small being the operative word. Not since the PowerBook 2400 had Apple had a portable this size and weight. But the iBook was much improved upon the 2400, although 2400 afficionados may disagree. The larger 12.1" display hosted a XGA resolution, a big improvement on the SVGA 2400's 10.4" LCD. As you'd expect, the internal architecture was much improved on its 2400 predecessor, although the original G3/500 iBook with its 66MHz system bus did not represent any advance on the previous iBook architecture. Later iBooks have improved the internals incrementally.

Does the iBook traverse the full-sized notebook and sub-notebook markets? Yes, without a doubt. This is why many view its larger 14.1" sibling as an aberration which spoils the original 12.1" concept. It adds a larger screen, more overall weight (up to 5.9lbs) and no extra screen real estate (still XGA). The keyboard is also the same size. The main difference is the battery, which has a larger form factor and can power the iBook longer, up to a (claimed) 6 hours. Personally, I like the iBook 14.1, but also acknowledge the reservations expressed by devotees of the original iceBook concept. That doesn't take away from its immense popularity though (even in Japan, traditionally a market that worships small notebooks). Does the iBook 14.1 represent a triumph of form and function? Only in the marketer's mind...

The B List: Why They Don't Make the Grade

PowerBook G4 Titanium (2001- )

The TiBook is a controversial omission. It's a staggeringly-impressive piece of industrial design. But does it meet the design criteria? If the objectives were finish, screen size/quality and space-age strength, yes. But does it meet the design criteria established here? A resounding 'No'.

The TiBook is a controversial omission. It's a staggeringly-impressive piece of industrial design. But does it meet the design criteria? If the objectives were finish, screen size/quality and space-age strength, yes. But does it meet the design criteria established here? A resounding 'No'.

Why not? First, beyond the G4 chip in the original TiBook, this PowerBook breaks no new technological ground; its internal architecture is the G4/350 of the PowerBook series: a G4 grafted onto a G3 motherboard. No new memory bus design, no improvement in bus speed, not even a new video card.

Is it durable? Probably not, according to much anecdotal evidence. Its titanium skin dents far too easily and obviously; the paint flakes off, necessitating touch-up paint; hinges have proven less than reliable and horrendously expensive to fix, necessitating replacement of the case itself.

Performance? Embarassingly similar to the Pismo in its initial 400/500MHz G4 incarnations. FireWire? Half the speed of iBook, introduced only months later. Expansion bay? Gone. Second battery? Gone. Easy hard drive replacement? Gone. Removable daughtercard? Gone. You get the picture.

Screen aside, there wasn't much beyond bragging rights that would convince die-hard Pismo owners to jump to Ti, but plenty of owners of earlier PBs did. Only in its current iteration is the TiBook really living up to its looks. But the design flaws are still inherent, and it's questionable whether Apple will opt for titanium or another metal as the basis for the next Pro PowerBook.

PowerBook G3 Series (Lombard and Pismo) (1999-2001)

Excellent designs both, which cleverly slimmed and lightened the original Wallstreet design, from which they are both derived. But that's what both of them are: derivative. Both added features incrementally under the hood, but these were not giant technological leaps in the way, say, the Duo Series was. Indeed, the iBook-derived keyboard represented a backward step from Wallstreet (I have both Wallstreet and Lombard; I like both keyboards, but the Wallstreet's is infinitely superior).

Excellent designs both, which cleverly slimmed and lightened the original Wallstreet design, from which they are both derived. But that's what both of them are: derivative. Both added features incrementally under the hood, but these were not giant technological leaps in the way, say, the Duo Series was. Indeed, the iBook-derived keyboard represented a backward step from Wallstreet (I have both Wallstreet and Lombard; I like both keyboards, but the Wallstreet's is infinitely superior).

There are some retrograde steps: only one CardBus slot (for example, I can't use a CapSure and a FireWire card at the same time, or a flash memory card simultaneously with something else); no modules other than a battery can be inserted in the left-hand bay; no internal floppy option; LocalTalk requires an ethernet adapter and you're restricted to a few, very few, serial printers using a USB adapter.

The slimness of the design means its met its design criteria of packing more features into a thinner, lighter, design, but this makes them more fragile than the Wallstreet [although perhaps not - yet - in the hinges department]. I often rest the Lombard on the closed Wallstreet lid. I really don't want do this the other way around.

PowerBook 1400 (1996-98)

Owners will take issue with this, but there can be no denying that the 1400 was simply the 5300 Apple should have built in the first place. The 1400 is almost unique among PowerBooks (next to the 2400) in having virtually no interchangeable parts with other 'Books. This, in the end, also counts against it.

Owners will take issue with this, but there can be no denying that the 1400 was simply the 5300 Apple should have built in the first place. The 1400 is almost unique among PowerBooks (next to the 2400) in having virtually no interchangeable parts with other 'Books. This, in the end, also counts against it.

The case design was pleasantly, if subtly, restyled, giving the 'Book a curvature not present in the oblong 5300/190 series. The keyboard was excellent for the time and an improvement on the 500/190/5300, and better than its 3400/Kanga successors, which used the same (5300) keyboard. The removable daughtercard made a welcome return, but the 500 had introduced this feature first.

But the internal architecture was simply carried over from the 5300, with the sole memory innovation (if it can be called that) being 'stackable' RAM modules. It added no additional RAM capacity (still 64MB) and merely caused added expense and complexity. Memory modules could not be mixed and matched far too often. The 1400's ROM refused to recognize more than 64MB. Batteries were still NiMH with poor performance on active-matrix models (and execrable on G3-upgraded 1400s). Video out, long a standard feature on all PowerBooks except the Duo, was pulled entirely and made an extra-cost option. Little bells and whistles - the Caps Lock light and floppy drive activity light - were removed. And this reeked of...cheapness.

Again, because the 1400 used the 5300 as its basis, the 117MHz base model still had no L2 cache, and all models still relied on the old Duo-based NuBus architecture. Like the 5300/190, Apple had failed to include Ethernet on the motherboard, and the old SCSI chip, now embarassingly slow, was retained. A good, solid 'Book, yes, no question. But innovative? Not unless you're counting case sleeve picture inserts. Pu-leaze. Gimme a break...